THE HUMAN RIGHTS CAMPAIGN: A LOOK INTO A SUCCESSFUL MODERN CAMPAIGN

- rosies

- Apr 10, 2022

- 11 min read

By Emma Barclay, Leading Graphic Designer of PR Committee 12 April 2021

TLDR: Abstract

Founded in Established in 1980 by Steve Endean and originally known as the Human Rights Campaign Fund, the Human Rights campaign strives to advocate for Americans who identify as members of the LGBTQIA+ community. In the early days of the campaign, the Human Rights Fund was primarily a fund in support of pro-equality members of congress. In 1995, the organization rebranded and changed its name, and, in addition, created their iconic blue and yellow logo. They now fight in support of those who identify as LGBTQIA+. The mission of the HRC is as follows:

By inspiring and engaging individuals and communities, the Human Rights Campaign strives to end discrimination against LGBTQ people and realize a world that achieves fundamental fairness and equality for all. HRC envisions a world where lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer people are ensured equality and embraced as full members of society at home, at work and in every community (hrc.org/about).

Much of their research and resources go towards fighting for those most at risk under current federal laws, specifically those who identify as transgender and/or are HIV positive. The HRC strives to provide resources and act as an advocate for small- and large-scale changes in laws to provide protections for LGBTQ+ Americans. Their success can be attributed to the mediated communication theories they utilize in their campaign. Their use of Design and the Three E’s paradigm combined with the Three Traditions of Social Change have allowed the HRC to become one of the world’s largest human rights organization.

1.2 Designing A Campaign

The design process of creating a campaign can be broken down into a few major components; focal segments, focal behaviors, and target audience.

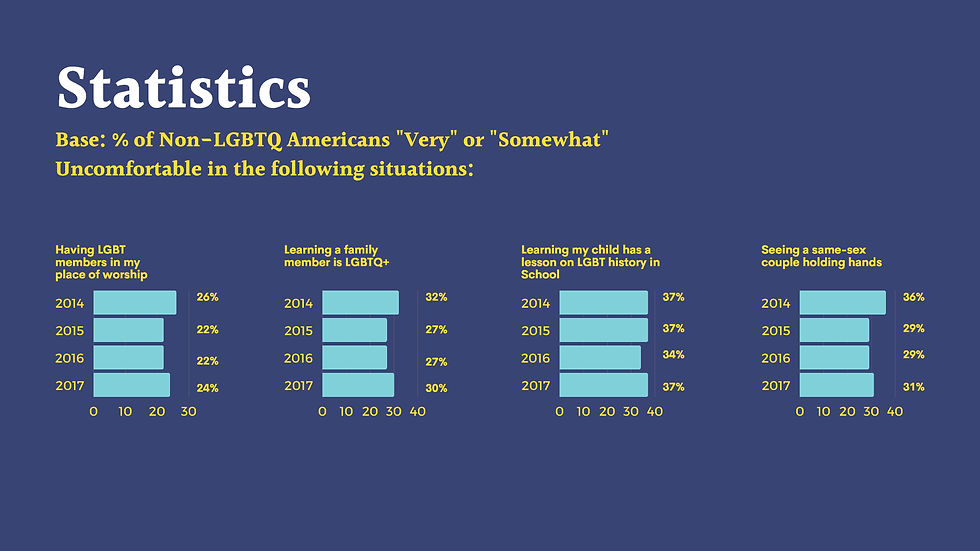

The focal segment of a campaign analyzes who is at risk if certain behavior is not changed. This can include socio-economic demographics, social subpopulations as well as psychological-based assumptions. In this case, those who are most at risk for unchanged behavior are those who identify as LGBTQIA+. The target audience of the Human Rights Campaign is not primarily the LGBTQIA+ community, but actually the portion of the nation that identifies as straight. The campaign’s goal is to gather support of straight citizens to serve as “allies” to the community by supporting local, state, and national legislation that gives protections to queer Americans. While the campaign does cater to those in the LGBTQ+ community, the second component of campaign design delves into how focal behaviors play a role in developing a successful movement. When looking at focal behaviors, a campaign designer must take into consideration the attitudes, beliefs, and social norms of an audience. According to a poll initiated by GLAAD and conducted by The Harris Poll, as of the year 2018, 26% of Americans feel “very” or “somewhat” uncomfortable having members of the LGBTQ+ community in their workplace, 31% feel uncomfortable seeing a same-sex couple holding hands, and 30% are uncomfortable knowing that a family member identifies as LGBTQ+ (pp. 2-3). While 30% may seem like a smaller portion of the population, in a country with 328.2 million citizens, 98.4 million people feel uneasy when regarding those who are LGBTQ+ (US Census Bureau, 2018). Although norms are beginning to skew in favor of more politically liberal ideologies, the Human Rights campaign targets those 98.4 million Americans as a part of their mission to normalize reproductive, educational, and health rights for queer Americans. By infiltrating typically conservative spaces, although drastic, the campaign can begin to expose and educate those who might not know the importance of equal rights and equal access to healthcare.

Finally, the third and arguably most important part of campaign design is looking into the demographics, psychographics, and social groups of a target audience. Different demographics include things such as race, gender, ethnicity, sexuality, socio-economic status, and geographic area. Certain demographics tend to have different qualities, such as religious background, political views and socio-economic differences. The Human Rights Campaign designs their campaign advertising by targeting middle to upper class Americans living in areas of the country where LGBTQ+ representatives are more likely to be elected. Their original targeted audience only advertised for these parts of the country, but now their reach has expanded slightly to middle to upper class Americans living in more politically liberal areas of the country, typically in more populated states and major cities. They are also expanding their reach to popular social media websites, such as Twitter and Instagram. The evolution of technology and mobile devices have greatly expanded their capable reach, now including young Americans using these platforms.

Psychographics tend to look more closely at people according to their aspirations, attitudes, and other psychological criteria, such as mental illnesses and overall mental state. The HRC offers resources for LGBTQ+ Americans for psychological counseling, medical advice, and other references for concerns regarding mental health. A large portion of their resources also include social issues, such as hate crimes, coming out in an unstable environment, parenting equality, and even resources for allies. They also engage with the HIV positive portion of the country, and applying many of their resources towards HIV testing, prevention, and treatment. Much of their target audience aspires to be politically active, specifically for national, state, and local political campaigns within the democratic party. Much of their focus lately has been on the Black Lives Matter movement, which has become a significant civil rights organization, gaining popularity and support after the shootings of innocent black Americans by law enforcement officers. A large portion of the BLM movement has been geared towards supporting transgender African Americans, specifically black transgender women. There has been a significant increase in collaboration between these two organizations, and many of their resources and advertisements overlap with one another when supporting LGBTQ+ African Americans.

1.3 Campaigns as Social Controls: The Three E’s

According to Atkin and Paisley, two media campaign scholars, there are three “E’s” that factor into the social change and contextual effectiveness of a campaign. The three E’s include the engineering, enforcement and education of a specific mediated campaign. The first E, engineering, has to do with the development of a certain technology that can help remedy a problem. The second, enforcement, manages the passing of laws and change on a greater political scale. Finally, the third E, education, engages with audiences to modify knowledge, attitudes, belief, and behavior. According to chapter seven of Public Communication Campaigns, education is “the predominant communication arm of social change” (Atkin, Rice, p. 104). It is important to note that this paradigm does not investigate or judge campaign planner’s motives. It is simply a system that groups campaign’s actions into three distinct categories in order to analyze its effectiveness.

While the Human Rights campaign may not completely align with engineering and enforcement as it does education, the campaign utilizes all three in its strategies. It can be argued that the rise of social media and technology have played a major role in the engineering of the Human Rights Campaign. The evolution of social media has allowed the campaign’s visuals and information to be spread around the globe, and therefore widening their audience by a considerable amount. It has allowed them to gain support in the way of donations, supporting political campaigns, and having a stronger voice when advocating for LGBTQ+ rights in a congressional, judicial, and presidential space. Although it is not a one-time-fix, the engineering of technology has expanded the reach so that the voices advocating for equal rights can amass in larger numbers and create positive change at a faster rate.

As aforementioned, the Human Rights Campaign, originally known as the Human Rights Campaign Fund, stared by exclusively supporting candidates that creates positive change for those in the LGBTQ+ community. By campaigning for certain candidates and donating money to their campaigns, the HCRF found that after:

"An election-night poll of people who voted in the 1994 elections [it] showed that the voters who changed the face of Congress continue to support ending discrimination against lesbian and gay Americans. In what the Human Rights Campaign Fund asserts is the first ever post-election poll that measured voter attitudes toward gay people, majorities of Republican, Democratic and Independent votes supported equal rights for lesbian and gay people, who face widespread and legal discrimination with no protection from federal law” (Off Our Backs, 1995) (p. 4).

The organization then went on to raise “cautions on its website that the data it collects on University and governmental positions ‘represent its best efforts to track laws and policies that relate to sexual orientation and gender identity’” (Steward, Working towards equality, 2003) (pp. 1-2). The Human Rights Campaign has a long-standing tradition of being incredibly active in the political space and has had great success advocating for protective laws to be passed. The enforcement of these laws has greatly expanded the protections for LGBTQ+ Americans.

The educational aspects of the Human Rights Campaign are easily the backbone of the movement it supports. Education in a campaign consists of modifying knowledge of the people in order to change attitudes, and the HRC does just that. Their website contains hundreds of articles with statistics and information, as well as the aforementioned resources for LGBTQ+ Americans in section 1.2. While their original purpose was to support candidates for political office, the HRC now offers educational resources for the LGBTQ+ community and straight allies that have been able to spread to a mass audience around the world.

1.4 Human Rights Campaign in Relation to Human Rights Campaigns

A technical human rights campaign is based off of one’s humanness. There are three so called “traditions” of social change, as discussed in chapter three of the text and theorized by (Atkin & Rice, 2013) (pp.36-39). The first tradition has to do with access to technology. As technology developed after WWII, there were increasing amounts of newspaper advertisements being made, and with the development of telephone, satellite radio, and eventually television and social media (Rice, Atkin, 2013). The second tradition encompasses two major theories; spiral of silence (Noelle-Neumann, 1974; Scheufele & Moy, 2000) and cultivation theory (Gerbner & Gross; 1976). This second tradition examines the natural effects of a mediated campaign, extending focus towards technology diffusion and institutional rules around technology to consider the effects it spreads (Atkin, Rice, 2013). The third and final tradition encompasses the persuasive and purposive nation campaign. It utilizes deliberate attempts to influence behavior, such as a strong use of emotional rhetoric. This can be achieved through television ads, social media presence, and even can come down to the design of the campaign’s visuals.

The first tradition is by far the fastest growing. As aforementioned, the technology boom experienced in the 2000s with the rise of social media and easy access to internet has greatly influenced and changed the way campaigns advertise and receive funding. The HRC has a website and multiple social media accounts, even allowing users to purchase merchandise in support of the campaign, increasing its popularity. Although some might not have access to internet, the vast majority of the country either owns a cell phone with internet capabilities or has access to a computer with internet. The target audience of the HRC, which includes middle to upper-class Americans, most often have this technology at their disposal. What must be considered of the first tradition, however, is the possible negative impacts technology and media framing can have on a campaign. As news has become more readily available with the 24-hour news cycle and the rise of social media, the news media can frame human rights issues to sway a portion of the population one way or another. One instance in particular stands out. Even under allegations for sexual misconduct,

"Roy Moore and Republican leaders have urged him to end his run for U.S. Senate in Alabama, Mr. Moore is relying on his most loyal constituency to keep his campaign afloat– evangelical Christians” and that:

Many conservative Christians see a man who has defended values--including opposition to abortion and same-sex marriage, and an expanded role for religion in the public sphere--that they believe are under siege, and they are reluctant to abandon him” (Lovett, 2017).

Although the media has many positive effects on human rights campaigns, the media has the same effect on opposing sides. The same unification that LGBTQ+ activists have with the HRC occurs between conservative Christian users, specifically those against same-sex marriage. These opposing forces, while they do have power, are still too weak to be of any harm to a campaign such as the HRC. When battling for LGBTQ+ equality, there is a great discrepancy between those in support of LGBTQ+ equality as opposed to those who don’t. Those opposed to same-sex marriage greatly outnumber those in support of the HRC, however, the HRC’s fight for marriage equality and health care rights have actually assisted in the passing of same-sex marriage equality in 2014, and other progressive laws to protect LGBTQ+ equality.

According to the second tradition, natural media effects happen passively in most cases. The news we see often reflects our own views, especially since targeted advertising has become a major part of modern life. Cultivation theory, postulated by Gerbner and Gross in 1976, is “the argument that the stories that are at the core of media content may reinforce social status inequalities and the existing distribution of power in society” (Atkin, Rice, 2013) (pp.37-38). In the case of the HRC, this occurs through the messages of inequality for LGBTQ+ Americans, calling for political change in order to end inequality and stigma around queer relationships and health care rights. Their message is amplified by this inequality, and the organization, while mostly focusing on the success of protecting queer rights, also draws a lot of its audience from unsuccessful steps as well. When a certain organization, person, or other entity fights in opposition of their cause, the campaign is able to utilize those stories to create a strong feeling in their audience, therefore increasing the likelihood that someone will donate to the HRC.

The other major theory within the second tradition, the spiral of silence theory (Noelle-Neumann, 1974; Scheufele & Moy, 2000), postulates that those who feel like they are in the minority opinions are far less likely to express their views. Although support for LGBTQ+ equality is far less prevalent in American citizens than the opposition, the HRC partners with other organizations and features celebrities in their social media feed. Celebrities and other large organizations and companies carry a much greater audience than the HRC, and by partnering with these organizations, the Human Rights Campaign can effectively dominate the social sphere. As newer generations are becoming increasingly progressive, support for equality has a much greater presence, and the voices in support greatly outnumber those in opposition, especially on social media. This overwhelming support gives the campaign a much stronger appearance than those against marriage equality and equal protections than those who are outwardly against LGBTQ+ rights. The Human Rights Campaign, in relation to the spiral of silence theory, has been able to silence much of their opposition due to the fact that they seem to have the majority of users in support of their cause.

The third and final tradition encompasses purposive and content-specific uses of communication technology. Much of this revolves around persuasive articles, statistics, and especially the visual aspects of the Human Rights Campaign’s advertisements. Although their brand colors are blue and yellow, they feature the signature pride colors across their website, social media posts, and articles. The symbolic nature of the rainbow plays a large role in their visual brand and affirms its unification with the LGBTQ+ community. A large part of color theory encompasses the emotions that certain color combinations make people feel. One of the most prevalent symbols of the HRC is actually their blue and yellow bumper stickers. According to the HRC’s website:

In doing research for a bumper-sticker purchase order, staff member Don Kiser, now HRC's creative director, learned that a square logo — different from the traditional rectangular bumper sticker — would cost just pennies to produce. The logo sticker was — and still is — distributed to new and prospective members who, in turn, help draw attention to HRC's work by placing the sticker on their cars and windows” (hrc.org).

In addition to the original logo, other variations have had a strong effect on mass media. After introducing their red and pink logo variation in 2013, the HRC noticed that:

The campaign went viral, and celebrities such as George Takei, Beyonce, Martha Stewart and others helped draw attention to the movement. Millions of people shared the logo, countless memes were created in response, and Facebook saw a 120 percent increase in profile photo updates. The Internet was awash in red and displayed the growing support for marriage equality in the U.S. and the world. Today, the red HRC logo continues to be used by HRC to promote LGBTQ rights (hrc.org). While often overlooked in many communication studies, visual brand recognition is a major factor in gaining engagement, and is one of the most, if not the most, powerful and persuasive tools at the HRC’s disposal.

References

Atkin, Charles K. & Rice, Ronald E. (2013) Public Communication Campaigns: Fourth Edition. Print.

GLAAD & The Harris Poll. (2018). Accelerating Acceptance: A Survey of American Acceptance and Attitudes Toward LGBTQ+ Americans.

Human Rights Campaign. hrc.org.

Lovett, Ian. (2017). Roy Moore and Republican leaders have urged him to end his run for U.S. Senate in Alabama, Mr. Moore is relying on his most loyal constituency to keep his campaign afloat: evangelical Christians. https://www.wsj.com/articles/roy-moore-relying-on-evangelical-christians-to-keep-campaign-afloat-1511103647

Off Our Backs. Off Our Backs, inc. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20835025

https://www.glaad.org/files/aa/Accelerating%20Acceptance%202018.pdf

Steward, Doug. (2003). Working Towards Equality. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40252491. Published by American Association of University Professors. (pp. 29-33).

US Census Bureau. (2018). https://www.census.gov/topics/population.html

Comments